Sgiorgiom 2

The Apothecary Shop and Laboratory

1. Setting up of the Laboratory

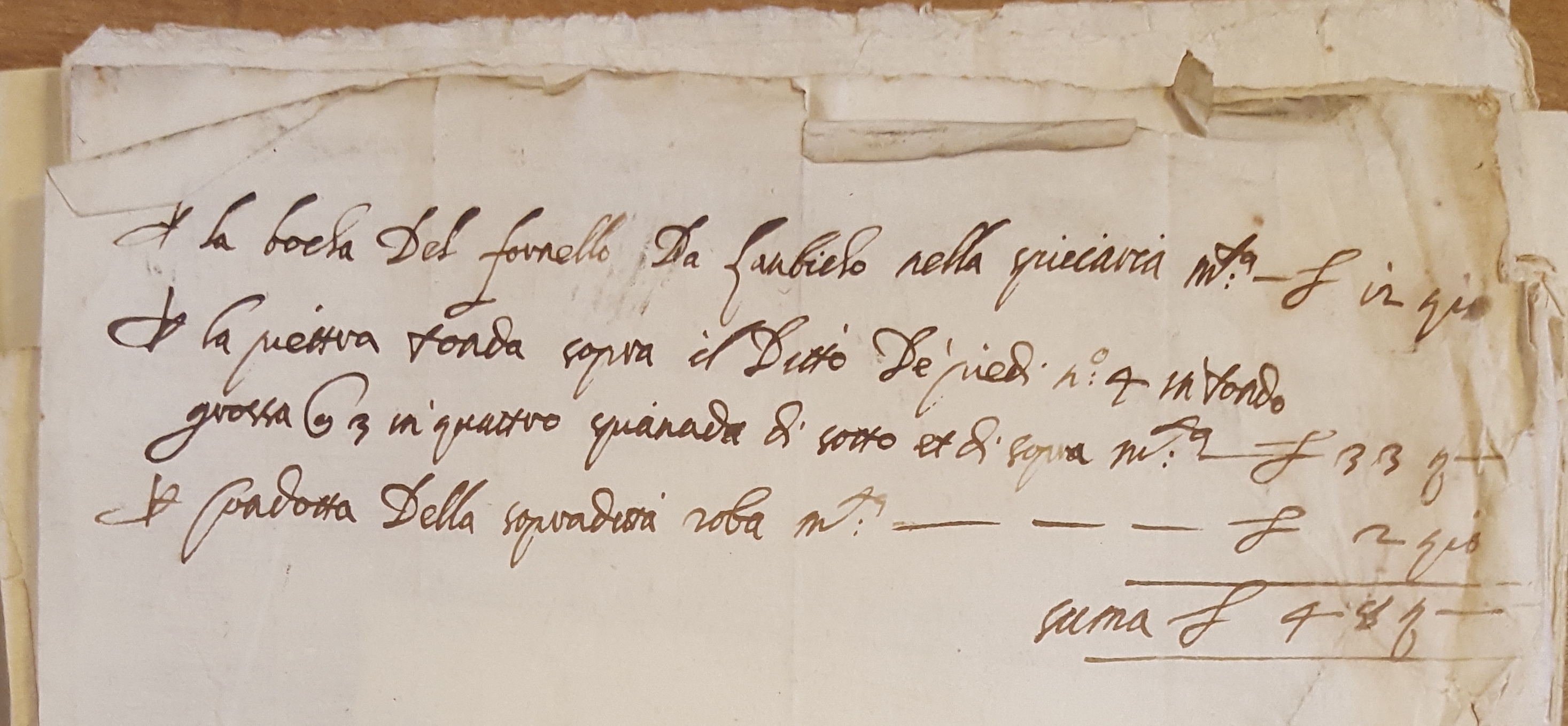

Documents in the Venice State Archives show that already in the first decades of the 16th century, the Benedictines of the Monastery of St. George had begun to run an adjoining apothecary shop. The maintenance and supply costs of this were recorded until the suppression of the monastery in 1806. The oldest document is a receipt from 1529 for the purchase of some equipment for the apothecary’s shop, which was therefore already in operation at that time.

Bill for the purchase of a kiln mouth for alembics, with associated round cover stone

Per la bocha del fornello da lambicho nella spiciaria monta L. 12 s. 10 Per la piettra tonda sopra il ditto, de piedi n° 4 in tondo, grossa oncie 3 in quattro, spianada di sotto et di sopra monta L. 33 s. — Per la condotta [trasporto] della sopraditta roba monta L. 2 s. 10”

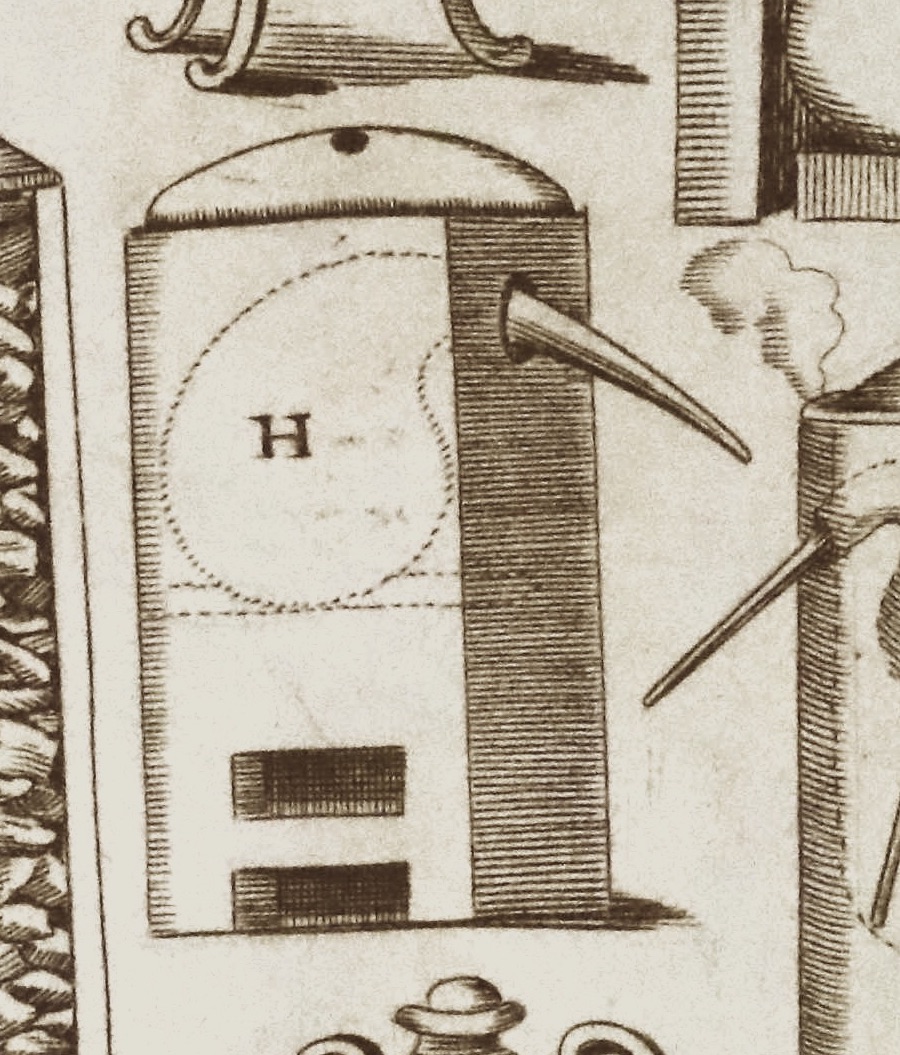

In Antonio de Sgobbis' famous 17th-century pharmacopoeia book, two engravings illustrate the variety of ovens and alembics that an apothecary could have at the time. The oven marked H (center of second row) is the closest model to the one described in the document shown above.

2. The 1629 Inventory

The oldest inventory of the Benedictines’ apothecary shop, which lists the substances possessed, the equipment, and finally the workshop books, dates back to 1629.

The apothecary shop in S. Giorgio Maggiore had three stills, one of which was reserved for the distillation of aqua-vitae, four bronze mortars, one lead mortar and one stone mortar. A very well-equipped laboratory indeed!

3. Books for use in the Apothecary Laboratory

At the end of the 1629 inventory, the titles of the books used for the laboratory are also listed: the “Libri della spetiaria”, which were indispensable guides for the handling of simples and the composition of medicines.

- 1604 Pietro Andrea Matioli medico per Bartolomeo Alberti n° 1 ➜

- 1572 [but 1602?] Jovannes [= Johannes] Mesue n° 1 ➜

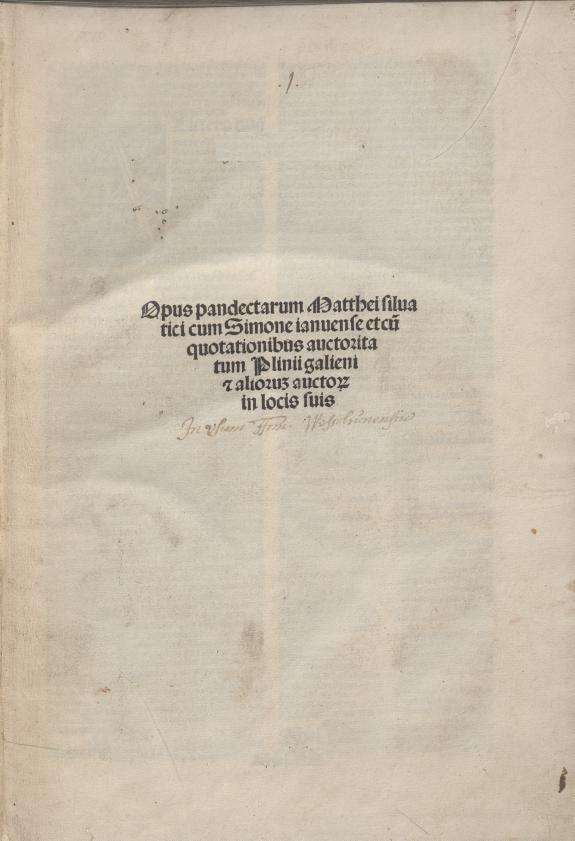

- Pandecta medicine Matthei Salvatici n° 1 ➜

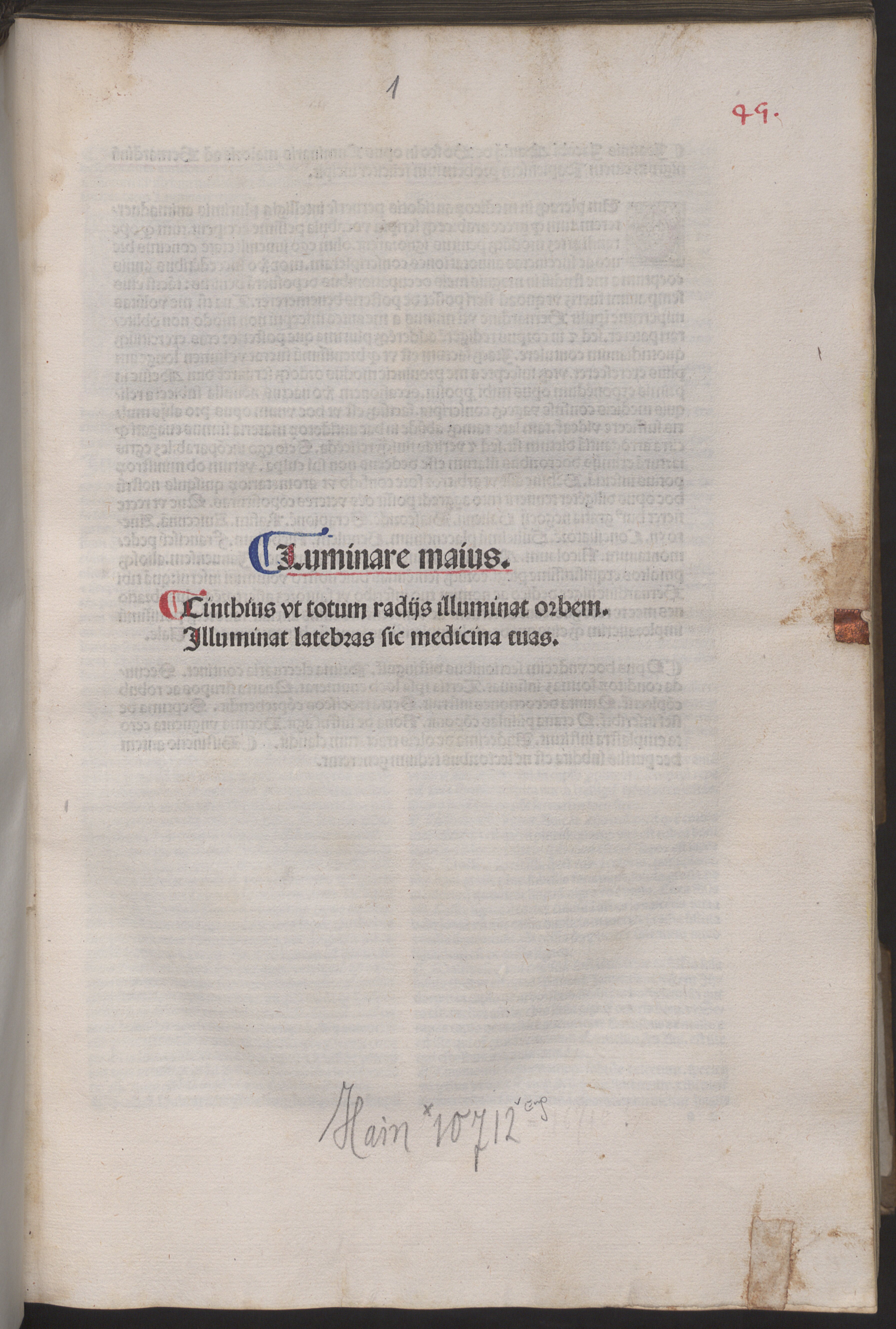

- 1496 Luminario [= Luminare] maius Jacobi n° 1 ➜

- 1524 Dispensarium magistri Nicolai n° 1 ➜

- 1548 Lexicon Grecum n° 1 ➜

- 1529 Pedacio Dioscoride Anaca… [Anarzabeo] n° 1 ➜ or ➜

- 1613 Discorso de Pietro Pagano piasentino n° 1 Not found. [Other work by Pietro Pagano: ➜

- 1596 [= 1586] Felippo Costa mantovano n° 1 ➜

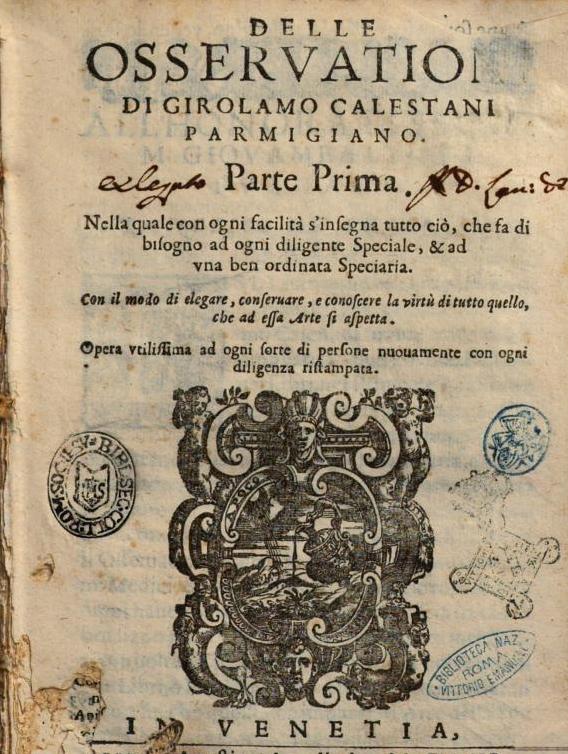

- 1606 Gerolimo Calestani parmigiano n° 1 ➜

- [1596] Giorgio Melichio n° 1 ➜

- 1585 Speculum Nataalli [sic] Vicenti n° 1 [Not found]

Listed first is a vernacular edition of the classic Dioscorides corrected and expanded by Pietro Andrea Mattioli, which could hardly be missing in an apothecary’s equipment for the recognition of the medical qualities of ‘simples’ (vegetal simples above all). The Benedictines also used a second copy of Dioscorides’ text in the orginal Greek language, accompanied by a Greek and Latin dictionary. Within the scope of the more traditional pharmacopoeia falls the Latin Mesue, a manual that was also the examination text on which aspiring apothecaries were tested to enter the Venetian Apothecary Guild (or better Collegio); as well as Matteo Silvatico’s Opus pandectarum, a 14th-century author from the Scuola Salernitana whose Pandectae were renowned for its accurate research into the virtues of herbs, and precise descriptions of plant morphology. Galenic pharmacy is well represented also by the Luminare Maius by Giovanni Giacomo Manlio, apothecary and botanist who wrote on Mesue’s groove by updating it between the 15th and 16th century.

But there is no shortage of the most recent pharmacopoeia texts either: the contemporary Dispensarium by the Tours physician Nicole Prévost, Girolamo Calestani’s up-to-date Osservationi and the Avvertimenti nelle compositioni de’ medicamenti per vso della spetiaria by Georg Melich, one of the greatest representatives of chemical pharmacy in Venice.

| The Garden in the Early Modern Age | The Apothecary Shop and Laboratory | The Balsamic Oil and its Herbs |